Lt Gen (Dr) JS Cheema, (Retd)

George Tanham identified ‘four key factors shaping India’s approach to power and security: geography, historical understanding over the past 150 years, socio-cultural beliefs, and British colonial rule.

Following the Allied victory in World War II, Britain perceived the Soviet Union as a major threat. The Indian sub-continent, particularly the Northwest Region, comprising Jammu & Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan, and the NWFP was ideal for establishing British bases for deploying forces to contain the perceived threat from the Soviet Union towards the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and the Far East. Karachi naval port and Peshawar air base were strategically located to target key Soviet installations.

J&K is also strategically important to both India and Pakistan. Sharing borders with Pakistan, Afghanistan, and China, J&K was India’s gateway to the then-Soviet Union. It provides control over the Chenab, Jhelum, and Indus rivers which are vital to Pakistan’s agrarian economy. J&K provides Pakistan with a contiguous land route to China, potentially enabling a coordinated threat against India. The NWFP now known as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa borders Afghanistan to the West, China to the North East, and J&K to the 1 East. The Khyber Pass provided a link between India and Afghanistan before independence.

British India, wanted the state of J&K, and the NWFP to be a part of the new nation of Pakistan to fulfil its perceived geostrategic role as a bulwark against the communist expansion. Britain felt that the real challenge to Britain and the West would come via Afghanistan. This was referred as ‘the uncertain vestibule’ and the challenge could be managed if Britain, after India’s independence could retain control of the Indian frontier from Pamirs to the Arabian Sea, i.e, control over Northern Kashmir, the NWFP, and Baluchistan – all territories West of the Indus river as it would provide them a vital link to influence events in Afghanistan.

J&K – a Muslim-majority State was a princely State ruled by a Hindu Raja, while NWFP was a British Province ruled by the Indian National Congress (INC). Britain based on the historical inclinations of Congress leaders was apprehensive of their staying in the Commonwealth and pursuing British imperial interests after independence.

The (INC), was the ruling party in most provinces of India including NWFP when World War II broke out in 1939. In protest against Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on behalf of India without consulting its leadership, the Congress Party resigned from the government in the provinces. The British Empire perceived this as an abdication of responsibility during a critical period. It reduced British dependence on the Congress Party to mobilize Indian resources for the war, which Jinnah adroitly exploited by promising the mobilization of resources for the British war effort. Jinnah was so delighted at the Congress Government’s resignations that the words ‘Himalayan blunder’ escaped his lips.

Jinnah, thereafter, openly started making demands for the creation of a separate state of Pakistan comprising the Muslims. This decision of the Congress Party made the British less confident of the INC as rulers of an independent India cooperating with Britain on defence and security matters. Instead, Britain gravitated more and more towards Jinnah. They perceived that independent India with her “socialist-minded Congress party, size, and potential would be difficult to manage and therefore it was prudent to partition the sub-continent to serve the twin objectives of creating a

Referendum in NWFP

Lord Mountbatten, was appointed the Governor-General on 22nd March 1947. He was specifically tasked to convince the Congress Party leaders to abandon their demand for the inclusion of NWFP in India, ensure after independence it would remain a member of the British Commonwealth as Pakistan was expected to do so anyway, and also persuade Jinnah to forego his claim for the whole of Punjab, Bengal, and Assam.

Britain decided to give freedom of choice to the Princely States and British Provinces about their future affiliations to the All-India Constituent Assembly. As INC was ruling the NWFP, Mountbatten appreciated its affiliation with India, and therefore, convinced Nehru to accept the referendum, which he did, and restricted the choice to join either India or Pakistan, as the Pathans were expected to opt for Pakistan.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, popularly known as ‘Frontier Gandhi, was a prominent NWFP leader who was deeply influenced by the Gandhian philosophy of non-violence. Fearing violence and massive abuse by the Muslim League supporters, he boycotted the referendum, to which Nehru and Patel acquiesced. The referendum, held on July 20, 1947, resulted in a narrow victory for Pakistan. Out of a total of 5,72,798 electorates, 2,89,244 or 50.49 percent voted for Pakistan. A mere 0.51%, or 5,690 votes, decided the province’s fate in favour of Pakistan.

Considering the narrow margin of its loss, it could be rightly presumed that had Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s Congress party supported aggressively by India participated in the referendum, NWFP could have opted for India.

India’s acceptance of the referendum and subsequently boycotting revealed pliability and failure to grasp the region’s geographical significance thereby forsaking national interest. Mountbatten assiduously manipulated historical socio religious beliefs and geographical affinity to accomplish the assigned mandate. NS Sarila rightly lamented “The last bastion from which the defence of India could be organized was evacuated without a fight and without the inclusion of NWFP, Pakistan would have remained an enclave within India and would have lost its strategic value to the West.” NWFP forming part of Pakistan provided geographical continuity to J&K and reinforced its ideological underpinnings of the two-nation theory.

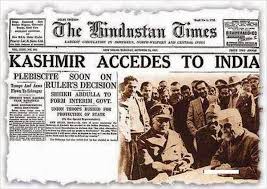

Accession of J&K Emboldened by NWFP’s Inclusion

Pakistan vigorously pursued its agenda for accession of J&K into its territory. The Pathan tribesmen of NWFP were readily available with the necessary motivation to acquire the additional adjacent territory by launching a tribal invasion in J&K. PM Nehru, due to political considerations delayed the acceptance of J&K’s accession.

Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of J&K, aspired for independence and wavered between India and Pakistan. Both nations wooed him. Pakistan, after signing a standstill agreement, abruptly reversed course, coercing the Maharaja by halting essential supplies, suspending the Sialkot-Jammu rail link, and infiltrating a column of raiders on September 3, 1947, into J&K as a prelude to a broader infiltration plan.

The Maharaja offered to accede to India in early and late September, but Nehru rejected the offer, demanding Sheikh Abdullah’s release and making him the head of a popular government, before accepting the accession to India. Nehru envisioned Sheikh Abdullah, a popular leader who opposed Jinnah’s two-nation theory, to act as a bridge between Kashmir and India symbolizing Indian secularism.

Sheikh Abdullah was released on September 29, but the Maharaja remained reluctant to relinquish power and become a figurehead in the country that his family had ruled for over a hundred years. Sheikh Abdullah’s popular movement centred around not just for democracy, but more specifically around the expulsion of the Dogra dynasty. The Maharaja’s request for arms and ammunition was rejected by Mountbatten, who insisted on first deciding on accession.

At the time of independence, India held a slight military advantage, with movable military assets divided in a 70:30 ratio. India possessed nine infantry divisions (88 battalions), an armoured division, an independent armoured brigade, two parachute brigades, and seven fighter squadrons, compared to Pakistan’s seven infantry divisions (33 battalions), an independent armoured brigade, a parachute brigade, and two fighter squadrons.

Indian Army was commanded mostly by its own officers, while, Pakistan’s Army was largely commanded by British officers. The Indian Army’s deployment of an infantry division plus an infantry brigade in East Punjab and an infantry brigade group plus an armored brigade in Hyderabad limited its availability for operations in J&K.

The numerical inferiority and lack of own officers did not deter Pakistan from planning to annex J&K. It made up this shortcoming by employing the local tribesmen, who were adept in operating in this type of terrain.

India established the Defence Committee of the Cabinet (DCC) on September 30, 1947, following Lord Ismay’s recommendations for national security’s highest decision making body. The DCC comprised the Prime Minister (PM) as the Chairman, the Deputy Prime Minister, the Finance Minister, and the Defence Minister. Notably, Governor General Mountbatten and not PM Nehru of India chaired the DCC’s first meeting, setting a precedent that allowed him to exert greater influence beyond his constitutional role until the end of 1948. This effectively allowed Mountbatten to influence key decisions regarding Kashmir, which proved detrimental to Indian interests. In contrast, Jinnah chaired Pakistan’s highest decision-making body and rejected Mountbatten’s offer.

India’s decision to allow the Governor-General to chair the DCC, while Pakistan refused, revealed a lack of strategic foresight, appeasement, and working under the Governor General’s influence.

Tribal Invasion of J&K

On October 22, 1947, Pakistan launched ‘Operation Gulmarg’, an armed invasion of J&K, deploying approximately 20,000 tribesmen supported by the Pakistani Army. The operation was intended to force the Maharaja to accede to Pakistan and, failing that, to annex the State by force. A sizeable portion of the Maharaja’s force deserted and joined the invaders, while the remaining forces fought valiantly despite being heavily outnumbered.

Meanwhile, in July 1947, the British-administered Gilgit Agency was transferred to J&K, but Pakistani-instigated Gilgit Scouts formed a rebel government. The Muslim soldiers of an Indian battalion sent to Gilgit joined the rebels. The raiders consolidated Gilgit and seized Skardu in August 1947.

On October 25, 1947, the DCC discussed the tribal invasion of Kashmir. Mountbatten opposed deploying the Indian Army to Srinagar, insisting that military action against J&K, a sovereign state, was contingent on Maharaja’s accession to India. He argued that sending troops into a ‘neutral’ state would provoke Pakistan to do the same, triggering an inter-dominion war.

Mountbatten’s rationale, that Pakistan’s potential intervention would lead to war, was illogical and biased, despite the worsening ground situation. India’s intervention, following the ruler’s request, would have been legally sound under international law, as no request was made to Pakistan.

Patel argued strongly for India’s right to assist a friendly state under invasion, characterizing it as a legitimate act of counter-intervention20 against Pakistan’s aggression. By delaying intervention, Mountbatten deliberately allowed the raiders to reach Baramulla. Mountbatten later conceded that sending troops at the request of a neighbouring country, even without formal accession, would be legally permissible, though he acknowledged the risk of Pakistani counter-intervention.

Mountbatten adroitly pushed forward British geostrategic interests, damaging India’s national interests.

By October 26, the tribesmen had captured Muzzafarabad, and Domel, and entered Baramulla, where they committed widespread atrocities. The Maharaja’s plea for Indian military assistance was again denied by Mountbatten, who maintained that intervention was contingent on the Maharaja’s accession to India.

The Maharaja signed the Instrument of Accession on October 26, 1947. However, there were sharp differences between PM Nehru and Deputy PM Patel in accepting the Instrument of Accession. Nehru insisted on a prior commitment from the Maharaja to include Sheikh Abdullah in the government. A frustrated Patel expressed his disapproval, stating, “I regret our leader has followed his lofty ideas into the sky and has no contact left with earth or reality.” The accession was finally accepted on October 27, and the Indian Army was airlifted to Srinagar to repel the invaders.

Had India accepted the accession in September, and then worked to integrate Sheikh Abdullah, the tribal invasion would not have reached the outskirts of Srinagar. This delay also exacerbated the power struggle between Sheikh Abdullah and the Maharaja. Nehru’s political decisions overrode strategic national interests, preventing the swift resolution of the conflict.

Upon announcing J&K’s integration into India, PM Nehru assured the people of J&K that a plebiscite would be conducted once peace was restored to determine their future. Similarly, Mountbatten with Cabinet’s approval, wrote to the Maharaja, suggesting a public referendum on the accession after the expulsion of the invaders. However, these assurances were legally not required. The sovereign ruler of J&K unconditionally acceded to the dominion of India in terms of the Indian Independence Act of 1947 and the Government of India Act of 1935, as amended, and did not require a reference to the people to settle the accession.

A Danish diplomat observed “The contents of the letter formulated in accordance with Mountbatten’s advice to the Indian Government, should later form the background of the basic conflict between India and Pakistan.”

The lack of strategic forethought, realpolitik, and vision on long-term national security in the Indian leadership is evident.

The Indian Army’s rapid deployment to Srinagar surprised Jinnah. The Army launched a counter-offensive recapturing Baramulla and Uri by November 1947. However, in the Jammu Region, the raiders surrounded Poonch, Mirpur, and Bhimber by November. 1947.

The DCC opposed Indian Army plans to liberate Poonch and other towns, with Whitehall viewing Indian control of Western Jammu as a threat to Pakistan. To protect the Jhelum Bridge and Mangla Headwork’s, the British Commander-in-Chief (C in-C) advised India against any offensive actions, though some towns were relieved.

Nehru’s decision to hold Poonch was opposed by Mountbatten and the British C-in-C, who deemed it risky, but Nehru stood firm to reinforce Poonch in November 1947 with an infantry battalion from Uri Sector. However, Mirpur and Bhimber, despite being strategically important were not prioritized and could have been captured by diverting additional forces from Punjab and Hyderabad.

Mountbatten’s diplomatic efforts to de-escalate the conflict failed due to the parties’ rigid stands. India then considered escalating the war into Punjab, proposing air strikes against raider bases within Pakistan. At a DCC meeting on December 20, 1947, India proposed a ten-mile cordon sanitaire, from Naushera to Muzaffarabad, to be heavily bombed by the Indian Air Force (AF). Mountbatten opposed this, citing civilian casualties and limited availability of aircraft, and instead suggested UN intervention as India had a ‘cast iron case.’

However, there was no constraint on aircraft availability. By December 1947, three squadrons were available and fully operational in Kashmir. Nehru, mindful of civilian casualties, reduced the scope of air operations. Mountbatten approved limited air strikes, fearing the cordon sanitaire would hinder a political 6 resolution.

Ultimately, Mountbatten pressurized Nehru to refer the Kashmir issue to the UN, fearing an all-out war. Nehru’s intention to launch a military attack in Pakistan Punjab was a coercive strategy while signalling strong resolve to the UK and USA.

It, however, backfired. Instead of the intended effect, it intensified pressure on him to refer the Kashmir issue to the UN. PM Attlee of Britain too urged Nehru to avoid war, warning of its “incalculable consequences” and the potential for international condemnation.

Ultimately, on December 20, 1947, Nehru reluctantly agreed to UN intervention. The Indian Cabinet, however, believed this was a prelude to military action if the raiders did not withdraw.

This belief, however, turned out to be incorrect. The decision to involve the UN proved detrimental, as the Kashmir issue thereafter became entangled in Cold War politics. British diplomats successfully swayed international opinion, emphasizing Pakistan’s claims based on Muslim majority and contiguity.

Britain’s primary motivation for pushing the UN referral was to avert a full-scale war, which would have significantly benefited India and would have led to the withdrawal of British officers from the Pakistani Army, including the Generals.

Had this occurred, the Pakistan Army, predominantly commanded by British officers, would have been significantly incapacitated. In contrast, the Indian Army, with its largely indigenous Officers, would have gained a substantial operational advantage in the plains of Punjab. Pakistan’s lack of domestic ordnance factories further contributed to India’s operational advantage.

Despite this, the Indian Army still had to keep J&K as the primary theatre of military operations due to the urgent need to evict the raiders from the maximum area of Kashmir. In January 1948, the Indian Army’s command structure was reorganized. On January 20, 1948, Lieutenant General KM Cariappa assumed command of the newly designated Western Command, replacing Lieutenant General Russell. The forces in J&K were restructured into the Jammu and Srinagar Divisions.

India by April 1948, had seven brigades in J&K, with another being inducted. The Indian offensive towards Uri-Domel could not make much progress due to the combined strength of the regular Pakistan Army and tribesmen as it had not factored in the presence of regular Pakistani troops.

The British C-in-C blocked a summer 1948 offensive towards Poonch, citing troop shortages due to the situation in Hyderabad, despite Nehru’s prioritization of the objectives. Later events confirmed that the Hyderabad situation proved less critical than claimed and the danger to East Punjab remained merely a threat.

A planned offensive towards Muzaffarabad was postponed in June 1948 to address the criticality in the Ladakh Region, where the Pakistan Army had captured Zojila, Kargil, and Dras. After repeated failures, Indian forces, employing tanks, captured Zojila on 7 November 15, 1948, and secured Dras, Kargil, and Leh by November 24.

The Indian Army, considering the geostrategic significance of the Ladakh region, showed remarkable flexibility and strategic forethought to shift the centre of gravity and secure the vital Ladakh Region. Attempts to relieve Skardu failed due to inhospitable terrain and strong Pakistani resistance. The Indian Army in the Jammu region recaptured Jhangar and Rajauri by April 1948 and relieved Poonch on November 20, 1948. The IAF provided crucial logistic support to the besieged Poonch garrison and effective air support during the fighting.

The British C-in-C directed General Cariappa to focus on stabilizing existing positions, effectively halting his plans to capture Mirpur and Bhimbar, citing a need to defend East Punjab against a negligible threat. Internal security concerns were exaggerated to limit the employment of the Indian Army. Cariappa’s biographer rightly noted that he appeared to be fighting two enemies – Army HQ headed by Roy Bucher and the Pakistan Army headed by Messervy.

In essence, India faced opposition from both the Pakistani military and British commanders, with the latter proving more obstructive and audacious than the combined strength of the Pakistan Army and the tribesmen.

Concurrent political negotiations between India and Pakistan failed due to Pakistan’s rejection of J&K’s accession. Pakistan demanded the withdrawal of Indian troops and the establishment of a neutral administration, effectively transferring control to Azad Kashmir forces. India rejected Mountbatten’s proposal to accept a UN-supervised plebiscite without any Pakistani concessions.

Stalemate and War-Termination

By late October 1948, a military stalemate appeared inevitable. The British C-in-C informed Nehru that expelling the invaders completely from Kashmir was unattainable, predicting a stalemate with only limited tactical gains.

Nehru concurred, recognizing the possibility of only incremental progress sans a decisive victory. He also expressed concern about potential foreign intervention or aid to Pakistan, which would prolong the war.

General K.V. Krishna Rao – the former Chief of the Army Staff believed the Indian Army could have cleared the remaining areas of J&K, but was halted by cease-fire orders.

Given India’s strength in armour, artillery, and air power, and the improved internal security situations in Hyderabad and East Punjab, up to three infantry divisions could have been deployed in J&K. While the complete liberation of J&K might not have been feasible, strategic objectives like Bhimbar and Mirpur or portions could have been captured. However, effective operations required Indian officers in senior command positions, as British officers were perceived to be undermining Indian interests. Military historian Ganguly argued that India’s reluctance to reclaim the remaining princely state territory stemmed from “pragmatic political considerations.”

Specifically, Sheikh Abdullah’s influence was confined primarily to the Kashmir Valley, with pro-Pakistani and Sheikh’s old rival Yusuf Shah holding considerable sway in areas beyond Uri and other places like Mirpur and Bhimbar. Given the difficulty in securing the local Muslim population, the Indian Army was discouraged from further advances.

By December 25, 1948, the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) brokered a cease-fire agreement, which took effect at one minute before midnight on January 1, 1949.

Conclusion

The British orchestrated partition as a politico-strategic act in continuation of their ‘divide and rule’ policy, using the ‘two-nation theory’ to continue their influence over the subcontinent. Their pro-Pakistan policy on Kashmir stemmed from “its desire to retain control of strategically vital regions bordering Afghanistan, Soviet Russia and China, in the hands of the successor dominion that was more useful to British interests in matters of defence.”

Britain’s geographical considerations underscore Robert Kaplan’s assertion that geography plays a pivotal role in shaping strategic and geopolitical realities. Pakistan by virtue of its geography became a successor to British regional ambitions.

The 1947-48 India-Pakistan War was a unique war in which the rival armies of India and Pakistan were led by British Generals, who with the support of Governor General Lord Mountbatten advanced their geostrategic interests, which were aligned with that of Pakistan.

The Indian leadership struggled to counter this challenge and failed to adapt to the power politics of the emerging Cold War dynamics.

Mountbatten’s technique of mediation was to propose a compromise solution and, when this was rejected by Pakistan, to seek a unilateral concession from the party over which he had real influence as exerted by Prime Minister Nehru].

Mountbatten’s astute diplomacy in conducting a referendum in NWFP and assiduously taking control of the DCC effectively disempowered India’s political leadership, exposing their pliability, and propensity to sacrifice national interests.

Mountbatten’s intense pressure on Nehru to refer the matter to the UNO was the last straw in the coffin as it internationalized the conflict and made J&K a ‘disputed territory’. The decision continues to bedevil India even now.

“Indian leaders remained plagued by the age-old weakness of arrogance, inconsistency, often poor political judgment and disinterest in foreign affairs and questions of defence.”

The Indian Army, despite these challenges, performed admirably and surmounted the manifold challenge with great aplomb, and professionalism.

From Pakistan’s perspective, the ‘End’ justify the ‘Means’. It secured one-third of the strategic area of J&K which broke India’s geographical link with Afghanistan and CARs. It is in full control over the Gilgit Baltistan region, with Skardu providing it the base for operations on the Siachen glacier.

Critically, it laid the long-term foundation of deep distrust amongst the people of J&K against the Indian nation that metamorphosed into a large scale proxy war in the late eighties. While it was anticipated that the war in 1948 would settle the matter of territorial dispute over Kashmir, it instead created enduring hostility. The British colonial influence that impacted India’s strategic thought continues to reverberate even today.